Take a moment to notice the chair you are sitting on, the hum of the heater, and the smell of the air in the room.

Everything you know about the world comes to you through perception, which is how your brain interprets signals from your senses. Philosophers use a thought experiment called the Brain in a Vat to ask a big question: how can we be sure those signals are coming from the real world?

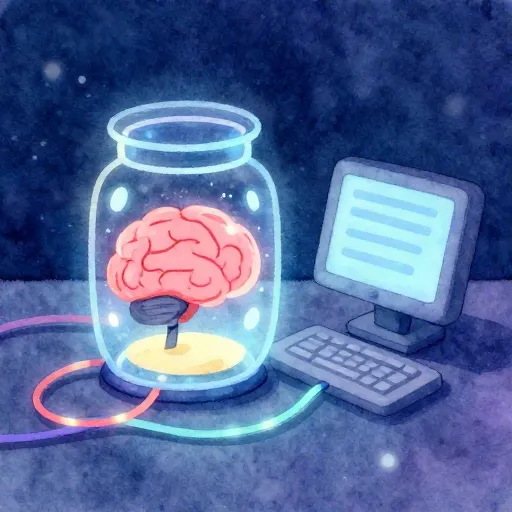

Imagine you are not actually reading this on a screen. Imagine, instead, that you are a brain floating in a jar of warm, salty liquid.

This jar is kept in a dark laboratory somewhere in the future. A team of clever scientists has hooked your neurons up to a supercomputer using thousands of tiny wires.

Imagine a room filled with silver machines that hum like a thousands bees. In the center, a clear glass jar holds a brain, floating in a glowing neon-blue liquid. Thin, rainbow-colored wires sprout from the base of the brain, snaking away into the back of a massive computer. Outside, the world might be a desert or a forest, but the brain only sees what the wires tell it to see.

Every time you think you are walking through a park, the computer sends an electrical pulse to your brain that says 'grass.' Every time you think you see a blue sky, it sends a signal that says 'blue.'

If the simulation were perfect, would you ever be able to tell the difference? This is the heart of skepticism, a branch of philosophy that wonders if we can truly know anything at all.

The Man in the Stove-Heated Room

To understand where this weird idea came from, we have to travel back to the winter of 1641. We are in a small room in France, where a man named René Descartes is sitting by a fire.

Mira says:

"Imagine Descartes sitting there in his fluffy robes, staring at a candle, and suddenly thinking: 'What if the candle is just a prank by a cosmic ghost?'"

Descartes was a mathematician and a thinker who lived in a time of great change. He realized that his senses had lied to him before, like when a straight stick looks bent in the water.

He decided to play a game of 'radical doubt.' He wanted to see if there was a single thing in the universe he could be 100% sure was real.

Close your eyes and press your fingers gently against your eyelids. You might see patterns of light or 'stars' even though your eyes are closed and the room is dark. Your brain is creating those 'sights' because of the pressure on your eyes. Can you think of another time your brain showed you something that wasn't actually there?

Descartes wondered if an Evil Demon was tricking him into believing in the world. He imagined this demon could make him feel the heat of the fire or hear the wind, even if the fire and the wind didn't exist.

This was the 17th-century version of a computer hack. If a powerful being was messing with his mind, how could he prove it?

I will suppose... some evil genius... has employed all his energies in deceiving me.

Why Your Brain is a Translator

It might sound like science fiction, but the way your body works actually makes this idea possible. Your eyes do not actually see 'trees' or 'dogs.'

Instead, they collect light and turn it into electricity. This electricity travels down your nerves to your brain, which translates the zaps into a picture.

Your brain contains about 86 billion neurons. These neurons communicate using electricity and chemicals. Every single memory you have, from the taste of an apple to the face of your grandmother, is stored as a specific pattern of these tiny electrical zaps.

Your brain is locked in a dark, silent bone-box (your skull). It never actually touches the sun or feels a cold ice cube directly.

It relies entirely on the messages it receives. If someone could intercept those messages and replace them with their own, your brain would have no way of knowing.

Finn says:

"So if my brain is just getting zaps... does that mean my favorite pizza is actually just a very specific electrical pulse? That makes me feel weirdly hungry for lightning."

This is why dreams feel so real while we are in them. When you dream of flying, your brain is receiving 'flying' signals, and it believes them completely until you wake up.

The Brain in the 1980s

Fast forward to 1981, three hundred years after Descartes. A philosopher named Hilary Putnam updated the 'Evil Demon' story for the age of computers.

He swapped the demon for a 'mad scientist' and the magic for a 'vat' full of nutrients. This version of the story became the Brain in a Vat theory we talk about today.

We can never be 100% sure that our senses are telling the truth. It is possible that everything we see is a clever trick or a computer program.

The world is too complex and consistent to be a trick. If I kick a rock and it hurts, that pain is real enough for me to believe the rock is there.

Putnam wasn't just trying to be creepy. He was interested in how language and thoughts work.

He argued that if a brain had always been in a vat, it couldn't even truly think about a 'tree.' It would only be thinking about 'tree-signals.'

Was it Zhuangzi dreaming he was the butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuangzi?

The World as a Video Game

Today, many people talk about this idea using Simulation Theory. They look at how fast video games are improving.

Forty years ago, games were just dots on a screen. Today, they look almost like real life, and soon we will have virtual reality that we can touch and smell.

Mira says:

"Maybe our whole universe is just a save-file on a giant computer in another dimension. I hope whoever is playing our game doesn't decide to delete it!"

Some thinkers, like Nick Bostrom, suggest that if any civilization ever makes a perfect simulation, they might make thousands of them.

If there are thousands of simulated worlds and only one 'real' world, what are the odds that we are in the real one? It is a bit like being one marble in a jar of a thousand identical marbles.

The History of Doubting Reality

Does It Actually Matter?

If you found out tomorrow that you were a brain in a vat, would you be upset? This is where philosophy gets really interesting.

Some people say it wouldn't matter at all. If the ice cream tastes good and your friends are kind to you, the 'reality' of the signals doesn't change the subjective experience of your life.

The idea of a 'simulation' isn't just for philosophers. Some physicists, like James Gates, have found bits of computer-like code in the mathematical equations that describe how the universe works. They haven't proven we live in a computer, but they found it very strange!

Others feel that the truth is the most important thing. They would want to 'unplug' from the vat, even if the real world was colder and less comfortable than the simulation.

This debate is famous in movies like The Matrix, where characters have to choose between a beautiful dream and a difficult reality.

Even if we are brains in a vat, we can still have a world.

Philosophy isn't always about finding the 'right' answer, because sometimes there isn't one. It is about the wonder of the question itself.

The fact that you can even wonder if you are a brain in a vat proves that you are thinking. And as Descartes famously said, if you are thinking, you definitely exist in some way.

Something to Think About

If a scientist offered you a 'Experience Machine' that could give you a perfect life in a vat, would you go in?

There is no right or wrong answer. Some people value the 'truth' of the real world, while others think happiness is real no matter where it comes from. What do you think makes a life 'real'?

Questions About Philosophy

Is the Brain in a Vat actually possible?

Does this mean nothing is real?

Who came up with the name?

Keep Wondering

The next time you look at a sunset or bite into an orange, remember that your brain is performing a miracle of translation. Whether the world is a simulation or a solid reality, the fact that you can ask these questions is the most amazing part of all. Keep your eyes open, but keep your mind even wider.