Imagine you have one extra ticket to a theme park and five friends who all want to go. How do you decide who gets it?

For centuries, people decided what was 'right' based on old rules or what a king commanded. But a group of thinkers called utilitarians believed we could use reason and logic to find a better way. They came up with utilitarianism, a branch of moral philosophy that suggests the best choice is the one that creates the most happiness for the most people.

Imagine London in the late 1700s. The air is thick with coal smoke, and the streets are crowded with people moving from farms to the new, noisy factories. Many people are poor, and the laws often seem unfair or confusing. In the middle of this changing world, a man named Jeremy Bentham sat in his study with a radical idea.

Bentham didn't think we needed complicated religious rules or ancient traditions to tell us how to live. He thought we only needed to look at two things that every human, and even every animal, understands. These two things are pleasure and pain.

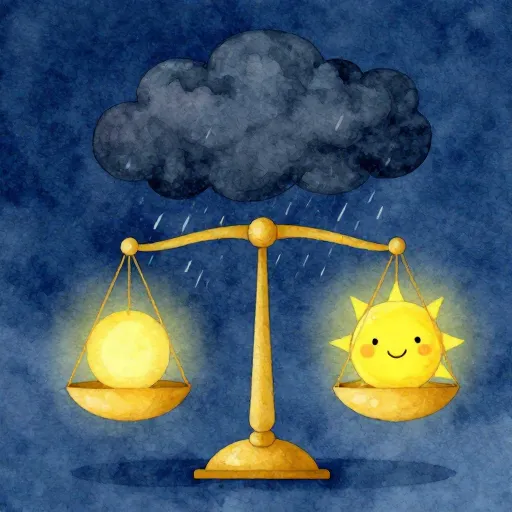

Imagine you are holding a giant set of golden scales. On one side, you put all the 'Ouch!' moments in the world. On the other side, you put all the 'Yay!' moments. Bentham believed that the goal of life is to keep the 'Yay!' side as heavy as possible.

Bentham believed that nature has placed us under the rule of these two masters. If something feels good, it is generally 'good.' If something causes suffering, it is generally 'bad.' This sounds simple, but it changed how people thought about everything from prisons to schools.

He called his big idea the Greatest Happiness Principle. It suggests that when you have to make a choice, you should pick the option that results in the 'greatest good for the greatest number.'

Finn says:

"Wait, so if a rule makes me sad but makes ten other people super happy, Bentham thinks I should just deal with it? That seems... tough."

To Bentham, this wasn't just a vague feeling. He wanted it to be as precise as science. He actually tried to invent a way to calculate happiness using a system he called the Hedonic Calculus.

He listed seven ways to measure a feeling, including how long the happiness lasts and how certain you are that it will happen. He imagined that leaders could sit down with paper and ink, do the math, and figure out exactly which laws would make the city the happiest place possible.

The greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation.

As Bentham's ideas grew, they caught the attention of a young boy named John Stuart Mill. Mill's father was a friend of Bentham and decided to raise his son as a 'genius' for the cause. By age three, Mill was learning Greek: by age eight, he had read more history books than most adults.

But as Mill grew up, he realized that Bentham's 'happiness math' had a bit of a problem. Bentham treated all pleasures the same. To Bentham, playing a simple game was just as good as reading a beautiful poem, as long as they produced the same amount of 'pleasure points.'

Next time your family is choosing a movie, try to use the 'Greatest Happiness Principle.' Don't just vote for your favorite. Ask everyone: 'On a scale of 1 to 10, how happy would this movie make you?' Add up the points for each movie. The one with the most points wins!

Mill argued that some types of happiness are 'higher' than others. He thought that using your brain to learn, create, or help others was a better kind of happiness than just eating a mountain of candy. He wanted to add 'quality' to the math, not just 'quantity.'

This shift was important because it moved utilitarianism away from just seeking fun. It became about flourishing and becoming the best version of ourselves. Mill believed that we should protect individual freedom because being free to choose is one of the highest forms of happiness.

Mira says:

"I think Mill is saying that learning to play the violin might be harder than eating ice cream, but the 'happy' you feel after practicing is a deeper kind of joy."

This way of thinking belongs to a family of ideas called consequentialism. In this view, the 'rightness' of an action depends entirely on its results, or its consequences. It doesn't matter if you had good intentions: if your action caused a lot of pain, a strict utilitarian might say it was the wrong thing to do.

Think about a white lie. Imagine your friend has a very silly haircut that they really love. If you tell them it looks great, you are lying, but you are also making them feel confident and happy.

Lying is always wrong because if we can't trust each other, the whole world becomes an unhappy, confusing place.

If telling a small lie prevents someone's feelings from being hurt or saves a life, it is the kindest thing to do.

In this situation, a utilitarian might say that lying is the right thing to do. The positive consequence (your friend’s happiness) outweighs the negative rule (don't lie). However, this leads to a very big question: is it okay to break any rule if it makes more people happy?

This is where the idea split into two paths. Act Utilitarianism looks at every single action one by one. You do the math for every choice you make. But Rule Utilitarianism suggests we should follow rules that, in general, lead to the most happiness over time.

It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied: better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.

Rule utilitarians might say we should never lie, because if everyone lied all the time, society would become a very unhappy and confusing place. Following the rule 'be honest' creates more happiness in the long run, even if it makes one person sad about their haircut today.

But what happens when the 'greatest number' of people want something that hurts a small group? This is the most famous criticism of utilitarianism. Imagine ten people who want to play a loud game of soccer in a park where one person is trying to sleep.

Finn says:

"But what if the majority of people decide they don't like someone? Does the math say it's okay to be mean to them? There has to be more to being 'good' than just counting votes."

If we only look at the 'greatest number,' the soccer players win every time. But is that fair? Philosophers worry that utilitarianism can sometimes ignore the rights of the individual. They worry it could lead to the 'tyranny of the majority,' where the many can treat the few however they want as long as they stay happy.

Even with these problems, the idea of utility (which is just a fancy word for usefulness or happiness) has shaped our modern world. When governments build a new highway, they use utilitarian logic to decide the path that helps the most drivers, even if a few people have to move their houses.

Through the Ages

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the idea expanded even further. A modern philosopher named Peter Singer argued that we should include animals in our happiness math. Since animals can feel pain, their suffering should be counted just like ours.

This leads to altruism, the practice of acting to help others. Some modern utilitarians try to calculate exactly where their charity money can do the most good. They might choose to buy 100 mosquito nets for a village far away instead of one fancy computer for themselves, because the 'total happiness' created is much higher.

The question is not, 'Can they reason?' nor, 'Can they talk?' but, 'Can they suffer?'

Jeremy Bentham was so dedicated to his ideas that he asked for his body to be preserved after he died! You can still see his 'Auto-Icon' (his skeleton dressed in his clothes) in a glass case at University College London today.

Utilitarianism asks us to be unselfish. It asks us to step back and look at the whole world, not just our own lives. It suggests that our own happiness is exactly as important as everyone else's: no more, and no less.

It is a philosophy of scales and balances. It invites us to imagine a world where every action is a pebble dropped into a pond, creating ripples of feeling. Our job, according to the utilitarians, is to make sure those ripples are as bright and joyful as they can possibly be.

Think of a hospital. Doctors often have to use utilitarian logic. If they have a limited amount of medicine, they have to decide how to use it to save the most lives possible. It's a heavy responsibility, but they use 'happiness math' to be as fair as they can.

Something to Think About

If you had a 'Happiness Machine' that could tell you exactly what would make the world happiest, would you always follow its instructions, even if you disagreed with them?

There isn't a right answer to this. Some people think the machine would be the ultimate fair judge: others think being a human means making our own mistakes.

Questions About Philosophy

Does utilitarianism mean I have to give away all my toys?

Is utilitarianism the same as being selfish?

What if my 'happiness' hurts someone else?

The Math of the Heart

Utilitarianism doesn't give us all the answers, but it gives us a very interesting tool. It asks us to look past our own backyard and see how our choices touch the lives of others. Whether you're sharing a snack or helping to change a law, you're part of the big experiment to see just how much happiness we can create together.