Imagine standing on a misty mountain in Japan, where every stone, every waterfall, and every twisted pine tree has its own secret heartbeat.

This is the world of Shinto, the ancient belief system of Japan that tells us the earth is not a quiet object, but a living community. Through stories collected in books like the Kojiki, we meet the Kami, the thousands of spirits who shaped the islands and still linger in the wind today.

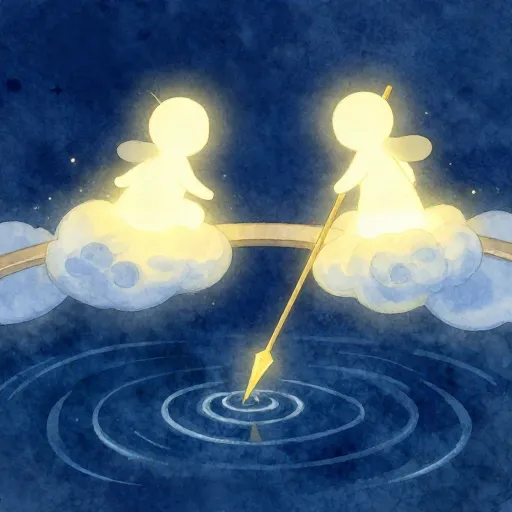

Long before there were cities or schools, there was the ocean. In the earliest Japanese stories, the world began as a messy, swirling soup of chaos. Two beings, Izanagi and Izanami, stood on the Floating Bridge of Heaven and looked down at the mist. They wondered what would happen if they reached into the dark water below.

They took a jeweled spear and dipped it into the ocean, stirring the salt and foam. When they lifted the spear, drops of water fell back down and hardened into the first islands of Japan. This was a world being born not from a factory, but from a simple act of curiosity and movement.

Imagine two figures standing on a bridge made of rainbows and clouds. Below them is only a dark, swirling fog. They reach down with a spear, and as they pull it back up, the salt on the tip hardens and falls. Splash! The very first island of Japan appears in the middle of the empty sea.

These islands were not empty places. Izanagi and Izanami went down to live on the land they had made, and soon the world began to fill with spirits. These spirits are called Kami, a word that is hard to translate because it means so many things at once. A Kami can be a powerful goddess of the sun, but it can also be the feeling you get when you see a particularly beautiful old tree.

To the ancient Japanese people, the world was crowded with these invisible presences. They called it the "Land of Eight Million Kami," which was their way of saying that the number of spirits was so high you could never count them all. Every river had a spirit: every mountain had a mood: every storm had a voice.

The world is not just what we see. It is also what we feel in the deep silence of the forest.

One of the most famous stories in this mythology is about the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu. She was the most brilliant of all the Kami, the one who gave light to the rice fields and warmth to the people. But Amaterasu had a brother named Susanoo, the Storm God, who was loud, messy, and very difficult to get along with.

After Susanoo caused a great deal of trouble in the heavenly palace, Amaterasu became so sad and frustrated that she did something unexpected. She walked into a deep cave, pulled a heavy stone across the entrance, and refused to come out. Suddenly, the entire world went dark: the crops stopped growing and the other Kami grew cold and frightened.

Finn says:

"If the sun went into a cave today, would we be able to make her laugh enough to come out? What kind of party would we have to throw?"

The other Kami didn't try to force the door open with hammers or angry words. Instead, they did something very human: they threw a party. They gathered outside the cave, lit giant fires, and began to dance and tell jokes. They hung a beautiful Mirror and a shimmering jewel from a nearby tree, hoping to catch her interest.

When Amaterasu heard the sound of laughter and cheering, she was confused. She wondered how everyone could be so happy while she was gone. She peeked out of the cave just a tiny bit, and her light hit the mirror the Kami had hung up. She saw her own brilliant reflection and was so amazed by the beauty that she stepped forward, allowing the other Kami to pull her out and bring light back to the world.

The Japanese Imperial family traces their history all the way back to Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess. This means that for over a thousand years, the people of Japan viewed their leaders as the direct descendants of the sun itself!

This story tells us something important about how the ancient Japanese viewed the world. They believed that even the sun can feel sad or lonely, and that the best way to solve a dark problem is often through creativity, community, and a little bit of noise. It also explains why mirrors are considered sacred objects in Japan: they are symbols of the light we all carry inside.

Japanese mythology isn't just about high-up gods in the sky. It is also about the strange and wonderful creatures that live in the shadows of our own world, known as Yōkai. These are the monsters, spirits, and tricksters of Japanese folklore. Some are scary, but many are just peculiar, like the Kappa, a water-spirit with a beak and a bowl of water on its head.

In Western stories, gods are often like people with superpowers who live far away in the sky. Some think Kami are just the Japanese version of Zeus or Thor.

In Japan, a Kami is often just the mountain itself. The mountain doesn't 'have' a god; the mountain 'is' the spirit. It's more about the energy of a place than a person.

If you were a child in Japan hundreds of years ago, you wouldn't just hear these stories in books. You would see the evidence of them everywhere. You might see a Torii gate, a tall red wooden structure that marks the entrance to a sacred space. Walking through that gate meant you were leaving the ordinary world and entering the home of a Kami.

Because of this, Japanese mythology created a deep respect for nature. You wouldn't want to pollute a river because a Kami lived there. You wouldn't want to cut down an ancient forest because the spirits might lose their home. This way of thinking is called Animism, the belief that everything in nature has a soul or a spirit.

To understand the Kami, one must first learn to be moved by the mystery of things.

Mira says:

"I like the idea that a teacup could have a spirit. It makes me want to be more careful with my stuff, just in case it's secretly awake."

As time passed, these myths didn't disappear. They changed and grew. When Buddhism arrived in Japan from China, the people didn't throw away their old Kami stories. Instead, they folded the new ideas in with the old ones, like mixing different colors of clay. They began to believe that the Kami were protectors of the new temples, and that the two religions could live together in peace.

In the medieval period, artists began to paint long scrolls showing the "Night Parade of One Hundred Demons." These were chaotic scenes of household objects, like old umbrellas or cracked tea bowls, coming to life as spirits called Tsukumogami. People believed that if you took care of your things, they would serve you well, but if you threw them away carelessly, they might come back to haunt you with a bit of mischief.

Go outside and find a natural object: a stone, a leaf, or a patch of moss. Sit quietly and look at it for one full minute. If this object had a spirit, what would its personality be? Is it a grumpy, ancient rock or a dancing, playful leaf?

Through the Ages

In the modern world, you can still see the fingerprints of Japanese mythology everywhere. If you have ever watched a Studio Ghibli movie, like Spirited Away or My Neighbor Totoro, you are seeing modern versions of these ancient spirits. The giant, fuzzy Totoro is a forest Kami, and the soot-sprites are a type of yōkai that lives in the corners of old houses.

Filmmakers and writers today use these myths because they help us talk about big, complicated feelings. When a character in a movie meets a spirit in the woods, it reminds us that the world is much bigger than our own concerns. It suggests that there are mysteries around us that we don't have to solve, but we should definitely respect.

In my grandparents' time, it was believed that spirits lived everywhere - in trees, rivers, insects, wells, anything.

Even today, many people in Japan visit shrines to leave a small coin or a prayer for the Kami. They aren't necessarily asking for magic tricks. Often, they are just saying "thank you" to the mountain, the sun, or the spirit of their ancestors. It is a way of staying connected to the long, winding story of the land itself.

Japanese mythology teaches us that the world is never truly empty or boring. If you look closely at a mossy rock or listen to the wind whistling through a bamboo grove, you might start to feel the same wonder that the writers of the Nihon Shoki felt over a thousand years ago. The "Eight Million Kami" are still there, if you know how to look for them.

Finn says:

"So, if everything has a Kami, does that mean my computer or my sneakers have spirits too? What would a sneaker-Kami even want?"

In Japanese myth, the number 8 is very special. It represents 'infinity' or 'a very large amount.' That's why they say there are 'Eight Million Kami' and why the storm god had to fight a serpent with eight heads and eight tails!

Something to Think About

If you were to walk through a Torii gate today, what kind of Kami do you think you would find on the other side?

There isn't a right or wrong answer. Mythology is a way for our imaginations to help us feel more at home in a world that is full of mysteries.

Questions About Religion

Are Kami always good?

What is the difference between a Yōkai and a Kami?

Is Shinto a religion?

The World is Listening

Japanese mythology reminds us that we are never truly alone. Whether we are in a crowded city or a deep forest, there is a sense that the world is watching, breathing, and participating in our lives. By learning these stories, we learn to look at a simple tree or a morning sunrise with a little bit more awe.