The average UK pocket money is about £7 a week: but if your child's best friend gets £15 and your budget says £3, you need a better answer than 'the average'.

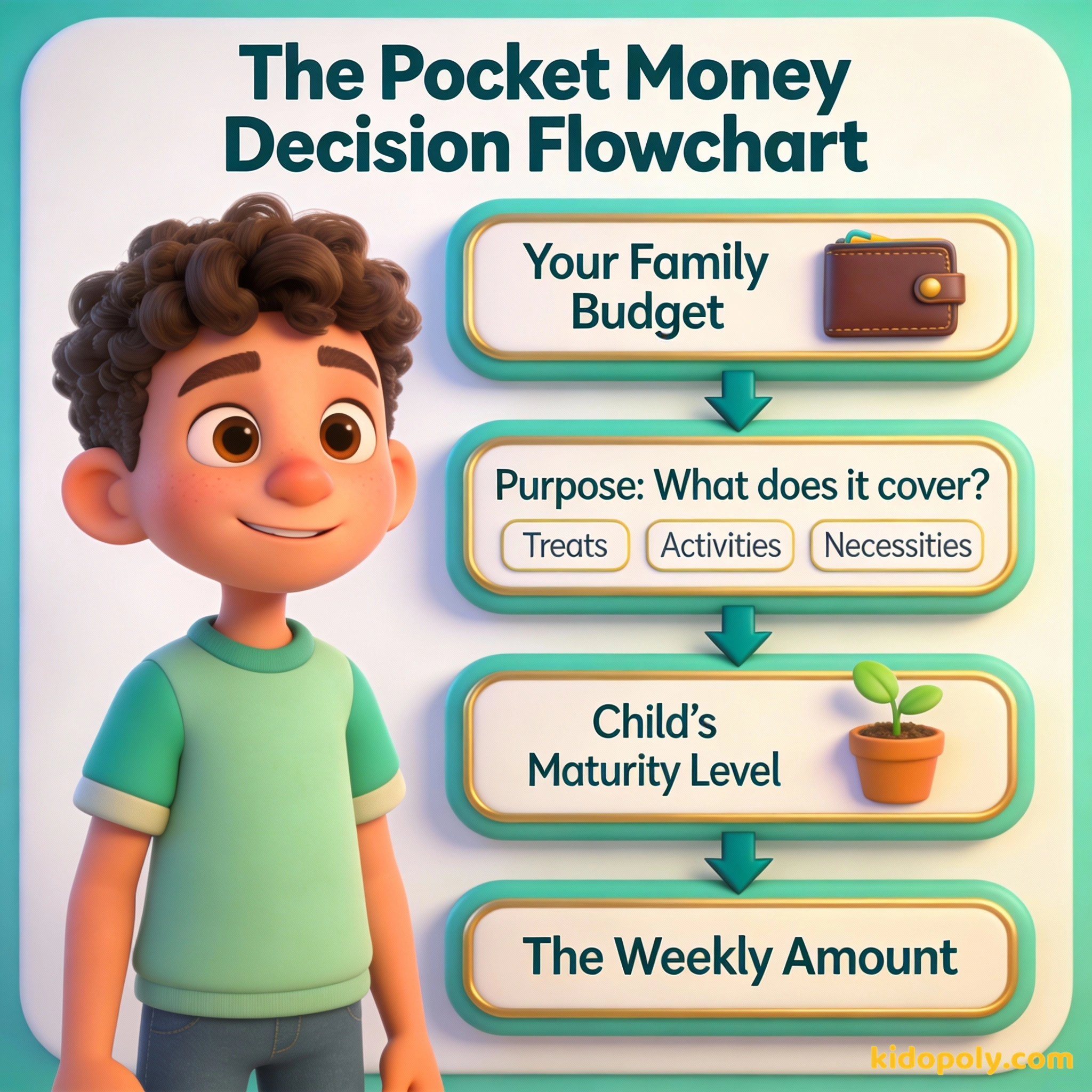

Deciding on a pocket money amount is one of the first major financial decisions you will make as a parent. This guide provides a decision-making framework based on your family budget and your child's financial responsibility levels.

Most parents start the pocket money conversation by asking what other people are doing. It is a natural instinct to want your child to feel included and keep up with their peers. However, the 'right' amount is rarely found in a national survey.

Imagine two families. Family A gives £20 a week, but the child must buy their own school lunches and bus pass. Family B gives £5 a week, but all necessities are paid for. Family B's child actually has more 'fun money' to spend, even though their pocket money amount is four times smaller.

While averages can provide a useful benchmark, they do not account for your specific household finances. They also do not reflect what you expect that money to actually buy. The goal is to find a number that challenges your child to make choices without causing family stress.

Pocket money is a training bra for credit cards.

The National Picture: UK and US Averages

To give you a baseline, current data from the Halifax Pocket Money Survey suggests the average UK child receives approximately £7.07 per week. In the United States, data from apps like RoosterMoney often shows a higher average of around $15.00 per week, though this varies wildly by state.

Finn says:

"If the average is £7, but my friend gets £10, does that mean his parents are better at money or just more generous?"

These numbers usually represent children across all age groups, from 5 to 16. Older children typically receive significantly more than younger children because their social lives and needs are more expensive. For a more detailed breakdown of these milestones, you can explore our guide on pocket-money-by-age.

According to the Halifax 2024 survey, 40% of parents say they have cut back on pocket money due to the rising cost of living. You are not alone if you need to keep the amount modest.

Framework: What Does the Money Cover?

Before you pick a number, you must define the scope of responsibility. If the money is only for 'extras' like sweets or a small toy, the amount should be low. If you expect them to pay for their own cinema tickets or hobby supplies, the number must be higher.

The 'Sweets Test': Give your child their weekly amount and take them to a shop. If they can buy everything they want without thinking, the amount is likely too high for a learning tool. If they have to put one thing back, you have found the 'sweet spot' for teaching prioritization.

Consider these three levels of responsibility:

- Level 1: The Treat Fund. The money covers only non-essential wants like snacks or small digital purchases.

- Level 2: The Social Budget. The money covers treats plus social outings like bus fares or entrance fees.

- Level 3: The Mini-Salary. The money covers wants, social life, and some necessities like clothing or mobile phone top-ups.

Mira says:

"I realized that if I give my daughter more money but make her pay for her own magazines, she actually spends less overall because she's more careful!"

The Family Budget Filter

Financial educators often suggest that pocket money should be treated as a line item in your household budget. It is a training expense for your child's future. You should never feel pressured to give more than your family can comfortably afford.

The 1% Rule: 1. Take your monthly household 'leftover' income (after rent/bills). 2. Calculate 1% of that total. 3. Divide that 1% by your number of children. Example: £500 leftover x 0.01 = £5.00 per week total. This ensures pocket money is sustainable for your budget.

One helpful rule of thumb is to look at pocket money as a small percentage of your disposable income. If the total amount for all children exceeds 1% to 2% of your monthly take-home pay, it might be time to scale back. Consistency is far more important for learning than the actual pound or dollar amount.

The goal is to give them enough money to do something, but not so much that they can do nothing.

Flat Rate vs. Earned Amounts

Some families prefer a flat rate where the child receives the same amount every week regardless of behavior or tasks. This creates a predictable environment for learning how to save. Other families prefer a variable model where extra money can be earned.

A reliable weekly amount helps kids practice long-term saving and budgeting without the fear of it being taken away.

Tying money to tasks or behavior teaches the value of hard work and the direct link between effort and reward.

While we cover the specifics of work-based pay in our chores-and-money section, it is worth deciding now if your base amount is a 'gift' or a 'salary'. Many experts suggest a hybrid approach: a small base amount for learning, with opportunities to earn more through extra responsibilities.

When and How to Increase the Amount

Your pocket money strategy should not be static. As your child grows, their financial literacy increases, and so should their control over a larger budget. Many parents choose to review the amount annually, often on a birthday or at the start of the school year.

Finn says:

"Is it better to get a little bit of money every single week, or one big chunk at the start of the month?"

When you increase the amount, try to increase the responsibility as well. If you give an extra £5 a month, perhaps they are now responsible for buying their own birthday cards for friends. This prevents the increase from feeling like 'free money' and keeps the focus on money management.

Financial independence is the ability to live from the income of your own resources.

Ultimately, the amount you choose should reflect your family values. Whether you use a pocket-money-chart to track it or a digital app, the focus should remain on the conversation. You are not just giving them cash: you are giving them a safe place to make mistakes.

Something to Think About

What is one specific thing you want your child to learn by managing this amount of money?

There is no right answer here. Some parents value the lesson of patience, while others want to focus on the math of addition and subtraction. Your answer will help you decide the amount.

Questions About Earning & Pocket Money

Should I give pocket money if I can't afford the national average?

Is it better to pay weekly or monthly?

What if my child spends all their pocket money immediately?

Your Next Steps

Now that you have a framework for the amount, the next step is deciding how to track it. You might consider using a pocket-money-chart to make the process visual, or look into specific apps mentioned in our allowance-for-kids guide. Remember, the amount is just the starting point for the conversation.